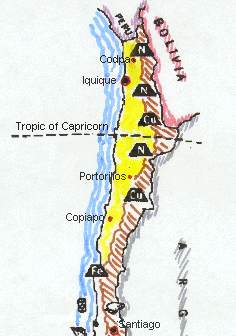

Much of the northern Atacama was mined for nitrates, an important ingredient in gun powder. In order to extract this "white gold" from the desert, towns were built, populations moved. In the years between the 1870s and the first world war, nitrate sales accounted for most of Chile's export earnings; and immense fortunes were amassed. Chile accounted for 65% of nitrate production in 1910. In 1914 the Germans, cut off from a supply of natural nitrate,

invented the Haber-Bosch process which fixed nitrogen from the atmosphere. By 1920 the nitrate boom collapsed and by 1950 Chile provided only 3% of world production. invented the Haber-Bosch process which fixed nitrogen from the atmosphere. By 1920 the nitrate boom collapsed and by 1950 Chile provided only 3% of world production.

The mines closed, the towns were deserted. Given the preserving atmosphere of the desert, these towns stand today just as they were when their residents left. We were there on "The Day of the Dead" and many families had returned to the town of Humberstone to celebrate the holiday. Our guides decided that we'd get as good a taste of the deserted town by touring the industrial section, where the nitrate was brought to the surface and processed.

Now in the ghost towns of the American west, one worries about stepping accidently on a rattlesnake, scorpion or other unpleasant desert animal; that is not a worry in the Atacama where there are no animals, no insects, no birds. In a patio next to the administration building, there had once been a garden, we walked through dried plants and vines rasping in the hot wind, with an empty fountain in the center. It was an oasis, once, when people were there to tend to them.

|

invented the Haber-Bosch process which fixed nitrogen from the atmosphere. By 1920 the nitrate boom collapsed and by 1950 Chile provided only 3% of world production.

invented the Haber-Bosch process which fixed nitrogen from the atmosphere. By 1920 the nitrate boom collapsed and by 1950 Chile provided only 3% of world production.